Special feature: Data suggests the “3Ps” approach has become a compliance-driven exercise

Praeveni Global’s new data index shows governments’ prevention, protection and prosecution measures are designed to meet targets rather than deliver results.

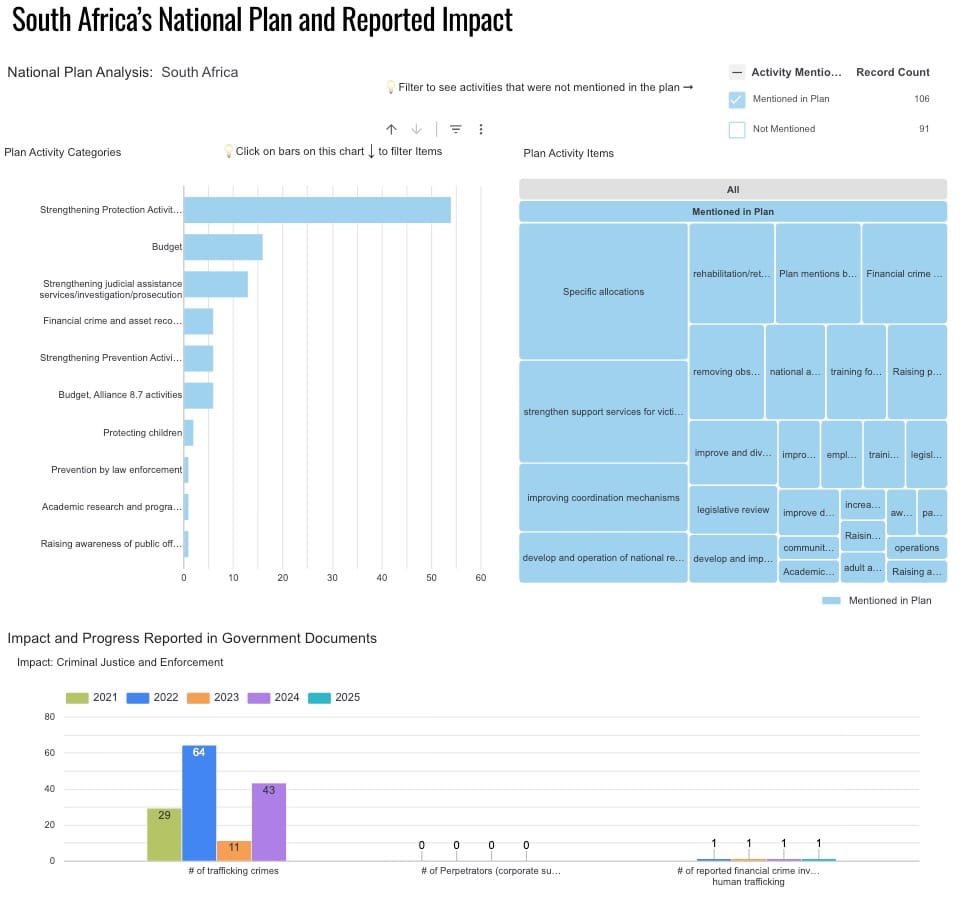

Governments’ flagship “3Ps” framework of prevention, protection and prosecution, long considered the foundation of global anti-trafficking policy, is no longer having a meaningful impact on trafficking outcomes, according to new data from Praeveni Global’s Modern Slavery Prevention Index. An analysis of recent and current national action plans entered onto the platform indicates that the measures developed under the Palermo Protocol 25 years ago have drifted from their original purpose and are now treated largely as checkbox targets rather than tools for designing effective, outcome-driven interventions.

Instead of using the 3Ps to shape balanced, holistic strategies, many governments appear to rely on the framework as a set of administrative headings under which they can catalogue easily reportable activities, Praeveni says. This shift has encouraged the creation of compliance objectives whose completion is simple to record but whose impact on trafficking or on victims’ real-world outcomes remains uncertain. As a result, countries can claim adherence to the 3Ps without demonstrating that these actions have meaningfully reduced exploitation.

Praeveni notes that the 3Ps model was never intended to function as an end in itself, nor to operate without accountability for measurable results. Its provisions were meant to be adapted to the actual conditions on the ground: the vulnerabilities affecting specific groups, the forms of criminal activity they face, and the wider economic and political pressures that heighten their risk of exploitation. The data suggests that this intended adaptability has been overshadowed by a focus on meeting targets rather than delivering impact.

Prevention efforts are now dominated by awareness campaigns, training activities, and interagency meetings, Praeveni says, while protection measures are focused on service provision but do not produce reliable data on victims. Meanwhile, prosecution is narrowly defined as legal action against traffickers, conviction rates are extremely low, and only the U.S. pursues a broad range of enforcement tools such as civil remedies, financial investigations, labour inspections, and corporate accountability.

This shift towards a system that rewards activity rather than results means governments often prioritize tasks that can be outsourced to NGOs or private contractors, avoiding reforms that would require deeper structural changes within government agencies themselves. The pattern also extends to multi-stakeholder partnerships with the private sector, which may bring in funding and visibility but can also create conflicts of interest and strategic confusion when those same actors need to be held to account, Praeveni observes.

A notable exception is border and immigration control: almost all national strategies link stronger border measures to a reduction in trafficking, assuming that tighter borders will have a direct effect. However, much of the cooperation reported between agencies consists of meetings and training sessions, which often serve as both the activity itself and the “outcome” being claimed.

Across the platform’s country analyses, there is a marked lack of detail of different forms of exploitation, Praeveni says. While plans and strategies rightly include detailed objectives on combating sexual exploitation, and most focus on child labour, wage theft is rarely incorporated into plans and strategies even though it is at the core of exploitation and coercion, and tackling it is essential to reducing vulnerability.

The Modern Slavery Prevention Index is a platform designed to provide a better understanding of the resources allocated by governments – particularly those of the G20 – to combat exploitation, including all forms of modern slavery. It seeks to determine the extent to which governments are taking action to reduce structural precarity and create safe environments in which vulnerable populations can retain the benefits of their labour and improve their quality of life, by analyzing the plans and strategies governments have formulated to counter exploitation, their commitments and objectives, the impacts sought, and the resources made available.